I am proud of the firm’s participation in Architecture 2030, Mindful Materials, and our numerous projects that connect with sustainability initiatives. I am proud of how this commitment to sustainability is present in our work every day. I am also proud of the teamwork behind our projects that go beyond expectations – SRG designers question the impact of the built world on our bodies and on our environment and proactively soften that impact.

Sustainability is a part of good design. At SRG, we focus on energy efficient systems and non-toxic materials that positively impact the health and comfort of the occupants, because everyone deserves good design. I wouldn’t say we made these decisions because we wanted a sustainability award, or because we wanted to meet a specific metric. We make these decisions in favor of sustainability, because it brings out our best work and gives our clients the best possible buildings that are made to endure. Ultimately, making sustainable buildings will help our planet (and ourselves) to survive into the future as the world continues to be affected by the long-term effects of global warming and climate change.

One of the little-known facts about SRG is that we are part of the Architecture 2030 Challenge and have been reporting our projects’ energy efficiency targets since 2014. We have in total submitted 68 different projects for a total of 131.8 million gross square feet.

SRG’s culture is based on continual improvement. As I sat down to write this, I asked myself how can we at SRG do better?

We can continue to look for opportunities to incorporate sustainable innovation in our practice and design exemplary buildings that serve our clients’ needs.

There are two SRG projects that come to my mind that can serve as models for us going forward. They show what can happen when the conversation of sustainability happens immediately and engages stakeholders and the community the building serves.

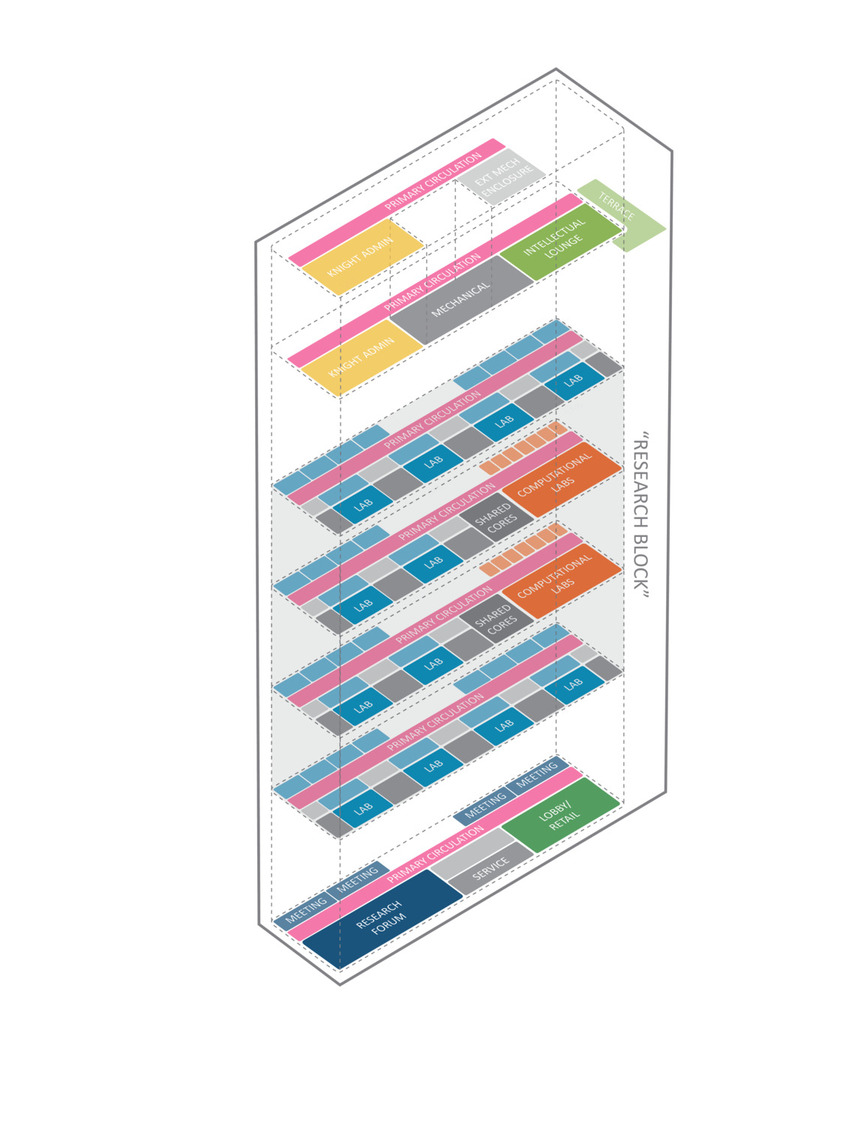

The Knight Cancer Research Building

Typical lab buildings are energy hogs. Due to the use of chemicals for research, air can’t be recirculated like it typically is in an office building. There is a lot of demand for energy to control lab environments and run the necessary equipment for research. It’s very challenging for a lab building to achieve LEED Platinum.

KCRB is not your typical lab building.

Our team evaluated every opportunity to enhance the building and drive more value for the client, pushing beyond the minimum metrics.

We tackled the LEED V4 material suite and utilized the new Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) tool to evaluate the impact of our structural system decisions. We evaluated a long-span post tension concrete structure that provided an extremely flexible lab space which also eliminated almost half of the building columns. This design strategy saved a significant amount of concrete and reinforcing material. The analysis informed our design process and proved that the long-span structure could do triple duty for the project – it reduces greenhouse gas emissions by reducing extraction, shipment, and installation of materials that would have been required by a traditional structural design while simultaneously providing cost savings and long-term flexibility for the researchers.

When focusing on energy efficiency, we meticulously evaluated building systems. A robust air and water-tight thermal envelope was developed, and daylighting opportunities informed the building organization. But what we learned when working with the scientists who were going to live day to day in the building is that they are keenly interested in creating a healthy environment by utilizing building materials that are carcinogen and toxin free. This aligns with their mission to end cancer as we know it. SRG, in collaboration with our sustainability consultant Brightoworks, created a matrix that mapped product choices by outlining manufacturing and chemical content of the proposed materials, with a special focus on eliminating carcinogens in the built environment. This unique tool served to educate the owner and design team on the impact of all interior material decisions to reinforce a healthy work environment.

We spent time upfront selecting the best materials and designing the best structure and systems to exceed expected LEED and Architecture 2030 benchmarks, and the result is a building that will define new possibilities for lab sustainability.

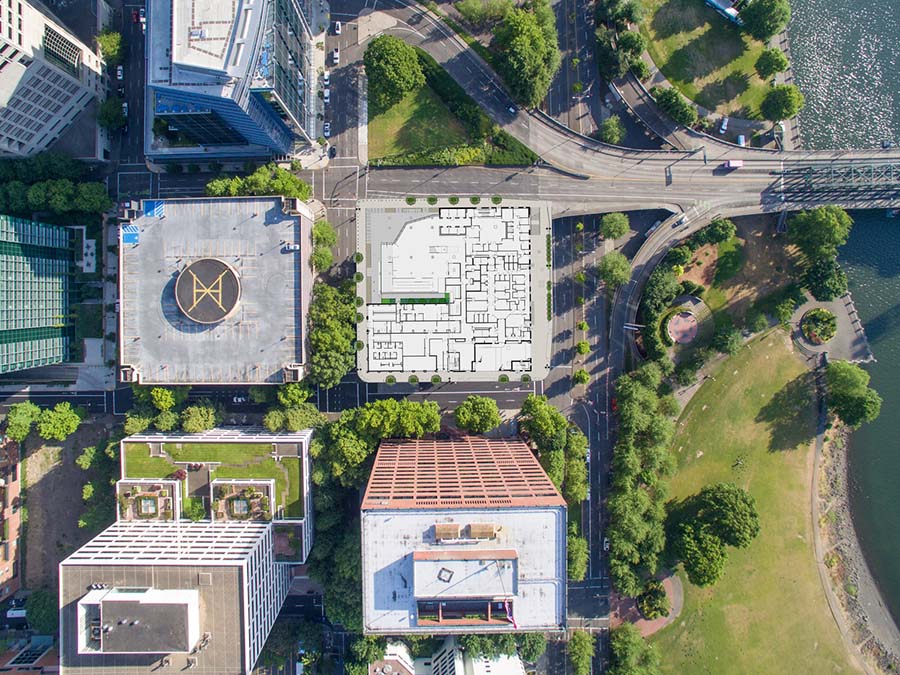

The Multnomah County Courthouse

For this project, SRG seized the opportunity to scale up our sustainability efforts and explore the concepts of integrated and place-based design on our what will be our largest building yet.

One of the most exciting aspects of the Courthouse from a sustainability perspective is its unique and prominent site. Located at the head of the Hawthorne Bridge in downtown Portland, this building will have a defining presence in our city’s skyline. It’s riverfront location also ensures that the east façade will remain unobstructed for the life of the building and offer spectacular views. Additionally, the uniquely composed façade coupled with the structural thermal mass is designed to capture the solar heat gain delivered by the morning sun. A radiant hydronic loop embedded in the concrete floor absorbs the energy that falls on the slab and redistributes it to other public spaces, reducing building heating loads on a clear winter morning by up to 20%. Tall ceilings in the corridor also accommodate clerestories, introducing daylight and views to nature for all the courtrooms throughout this 17-story building. Architecture 2030 targets will be achieved by combining: limited glazing, a high-performance envelope, radiant heating and cooling systems for judge and staff offices, and a displacement system for the courtrooms and public spaces.

In addition to passive energy conservation strategies, the Courthouse will also have an array of solar panels that will cover the project’s roof area. However, during weekends and holidays, when the building is unoccupied, the array’s energy production will exceed demands. The sensitivity of the downtown grid prevents the excess energy from feeding back into the system’s network, and on-site energy storage was found to be cost-prohibitive. The team got creative and looked to the iconic Hawthorne Bridge adjacent to the Courthouse, which happens to be connected to a separate radial power grid. The team, in collaboration with Multnomah County and Portland Gas and Electric, found a way to have the photovoltaics on the Courthouse bypass the building and ‘plug’ into the adjacent drawbridge to fully utilize the power being generated and offset the bridge’s energy costs.

These examples cover the energy efficiency strategies, but the Courthouse project has sought to push the environmental sustainability limits in every aspect of its design. We implemented innovative vacuum plumbing systems for water efficiency, collaborated with the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality to acquire Environmental Product Declarations for the structural concrete, and adapted a historic structure on the project site. Our holistic approach to sustainable design has the Multnomah County Courthouse on track to achieve a LEED V.4 Platinum Certification when it opens in spring 2020.

Communities can advocate for energy efficiency legislation.

We know that mandates help; there several examples, such as Seattle’s 2030 district. We at SRG are part of the grassroots effort to get similar legislation in Portland. Local, state, and federal government leaders can formalize efforts the design community is making for sustainability by instituting regulations and energy incentives. For example, the federal government under Obama mandated that new federal buildings had to achieve standards under 2030 and resulted in buildings like the Edith Green Wendell Wyatt Federal Building.

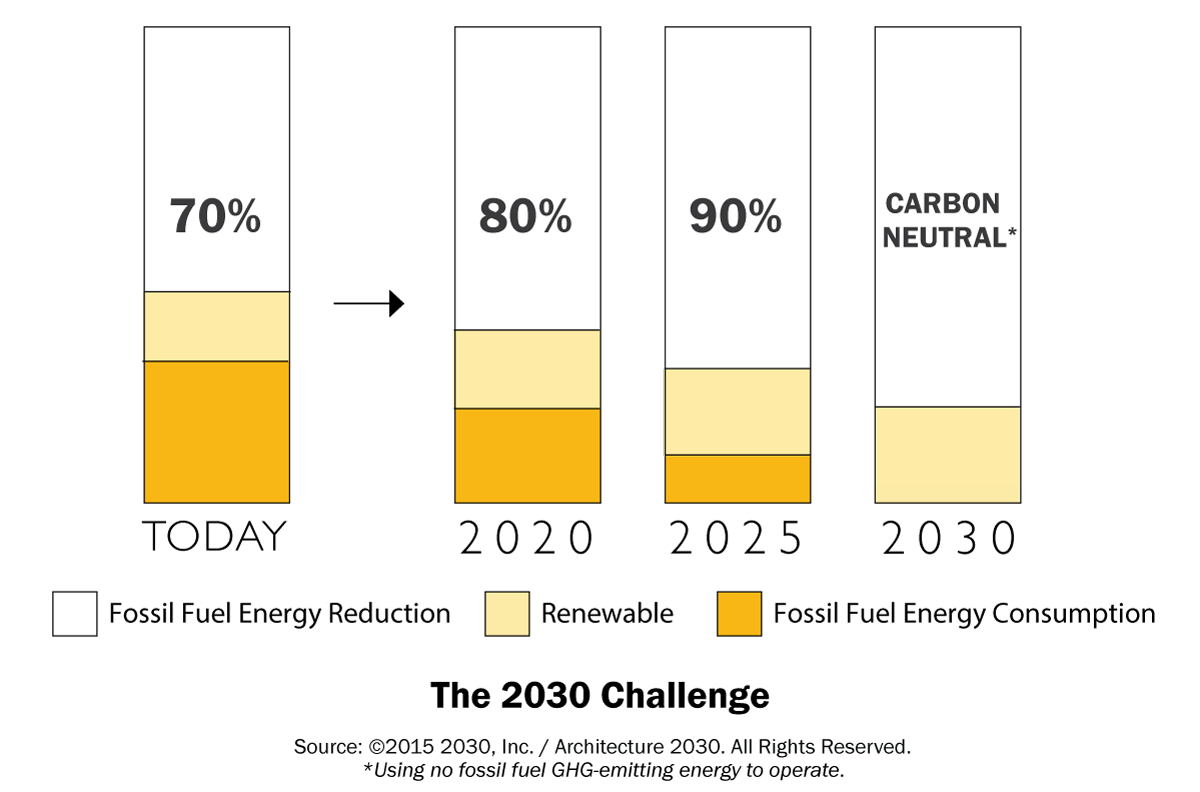

The entire industry needs to reinvigorate its commitment to sustainability by working harder to meet milestones for energy efficiency.

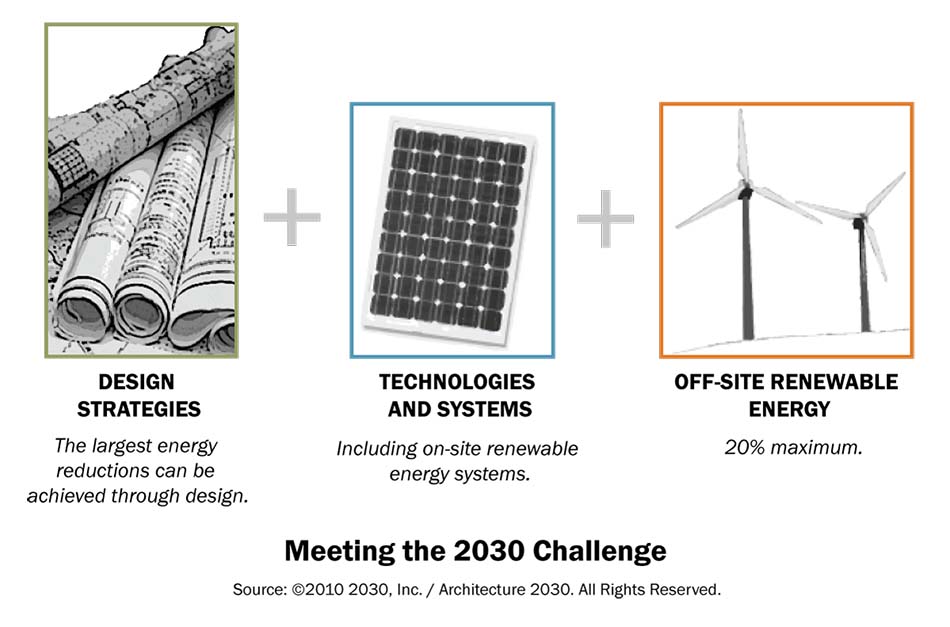

It can be disheartening when Architecture 2030 benchmarks have been missed, and we need to get better. It’s a dynamic challenge with a constantly moving target that’s meant to gradually eliminate energy sources that emit greenhouse gases. Institutions expect a building to serve for 50, 90, or 100 years. Structures need to be durable, flexible, and efficient. SRG is committed to developing energy efficient strategies and utilizing healthy materials on our projects, so that we do our part in meeting the 2030 challenge.