Living through the Tohoku earthquake and its aftermath made me reflect on how architects should prioritize resilience. Architects are not really thought of as “first responders.” In an emergency, I don’t think anyone has ever shouted: “IS THERE AN ARCHITECT IN THE ROOM ! ? ! ?” However, architects certainly do have a role to play preparing for resilience as we advise our clients on preparedness and use our creativity and forethought for space-planning and logistics.

How will buildings protect communities and help remobilize them after a disaster?

Most of my colleagues know that before joining SRG, I had been living and practicing in Tokyo for almost a decade. Earthquakes are just a part of life there. About 1,500 earthquakes strike the island nation every year. People are used to the early warning chime played over PA systems, TV and radio programs and cellphones, giving an average of 30 seconds notice. Minor tremors occur on a near daily basis, and a decent sized magnitude 5 or 6 might happen every couple of months. When that happened, my Japanese colleagues would likely just keep one hand on their mouse, maybe casually reach for a nearby model to keep it from tipping over, but otherwise, just keep clicking away.

Friday, March 11, 2011 was very different. It was one of those events that everyone remembers exactly where they were and what they were doing at the time it occurred.

I was on maternity leave at the time. My daughter was only a few months old. That day I had a meet-up with an English-speaking group of Expat Mums. I left the meet-up around 2:30pm, a little earlier than the other moms. As I was pulling out of the parking garage, my car started shaking violently. I thought for sure it was a problem with my engine or transmission.

I realized it was an earthquake when I saw tall buildings swaying around me. People started evacuating onto the streets. My baby was sleeping soundly in the back seat. I wanted to avoid getting stuck, so I decided to floor it... It was a ten-minute drive and whenever I stopped for a red light, I could still feel the road swaying. I arrived to find my husband there looking for us; he’d run home from his office.

Cell service was spotty, but TV reports warned of the possibility of a three-meter tsunami reaching Tokyo Bay. We quickly took stock of our situation. Our building was at sea-level on an infill island about 200 feet from the edge of the shoreline. Our second-floor apartment was in perfect condition. Not a book or dish out of place. Neighbors who lived on the upper floors were not so lucky. Their furniture turned over, every dish and book fell off the shelves, and there were big rips in the wallpaper. The gas service and elevators were shut down in fail-safe mode. At least one neighbor in a wheelchair had to be carried down 14 flights of stairs.

In five minutes I packed a go-bag: granola bars, instant rice packs, 2 liters of water, a roll of toilet paper, diapers and wipes, a cigarette lighter (neither of us smoke, I guess we thought to start a campfire) a pocket knife, our passports and 50,000 yen in cash - enough for three of us to go to Osaka by train - in a Ziplock bag. My husband packed a camping stove and huge wool blanket in a backpack and we ran back to his office, which was a newer building. We waited there for several hours with hundreds of his coworkers until the tsunami advisory for greater Tokyo was lifted.

At some point, I was able to phone my mom in Portland where it was the middle of the night. The call lasted about 30 seconds but long enough to assure her we were okay. By about 8pm Tokyo time, my husband and I were so exhausted from adrenaline, running around, checking on neighbors… we passed out on the bed - fully dressed, wearing shoes and with the baby between us. Meanwhile my mom stayed awake, watching in horror as the tsunami that hit further north was broadcast live on CNN. Ironically, we didn’t learn about the tsunami and subsequent partial, nuclear meltdown, until the next day when the magnitude of the situation started to come into focus.

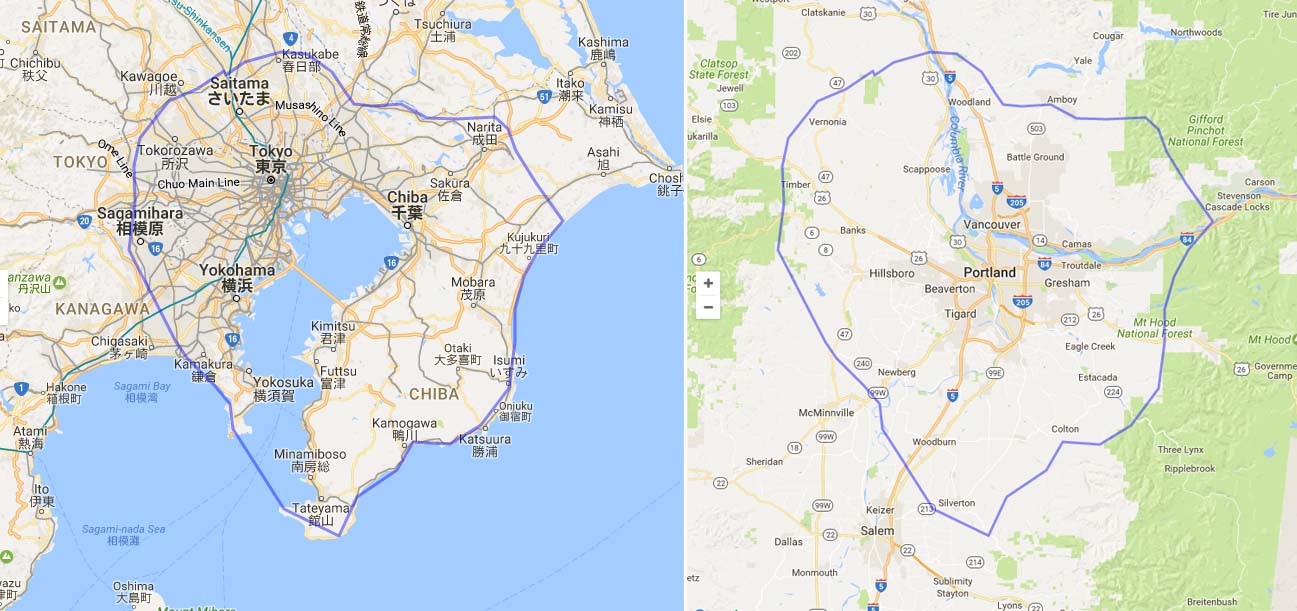

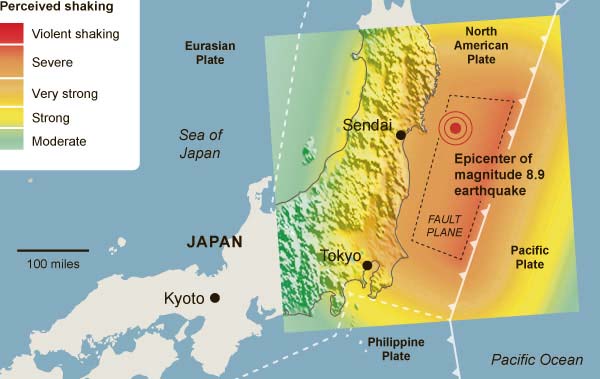

According to the Japan Meteorological Agency and US Geological Society, there were three distinct earthquakes that occurred within six minutes of each other with an average magnitude of 9.0. It was one of the most powerful seismic events ever recorded. It was centered on the seafloor 45 miles east of coast, at a depth of 15 miles below the surface, 231 miles NE of Tokyo. Additional stats from the disaster are startling as you can see here or in a detailed USGS report here.

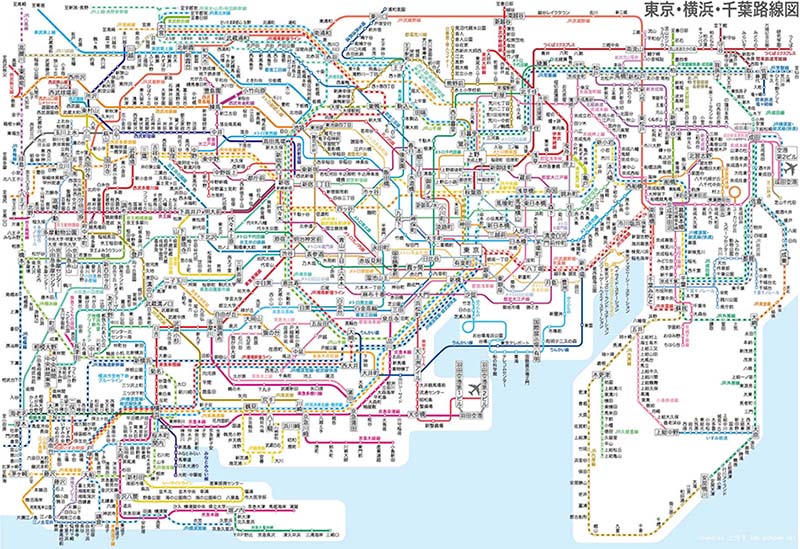

My husband reflected on experiencing the earthquake in his office. Thunderous noises came from the building itself as floors and window walls racked against each other. The shaking caused contents of bookshelves to fly out. Some of his coworkers screamed and cried and dove under their desks. Because all the subway lines and highways were shutdown as a precaution, millions of people faced the prospect of sheltering in place or enduring a very long walk to get home.

There were no reports of looting or price gouging but ATMs, gas stations, convenience stores and grocers, were cleaned out within hours. Sports shops sold out of tennis shoes and bicycles.

I later learned that those four other expat moms I’d been having lunch with got stuck at the shopping center complex which went into lockdown protocol. All customers were escorted up to the roof, in the freezing cold, to ride out the tsunami advisory. They were stuck there for hours with their babies, challenged by the language barrier and unable to communicate with their husbands. Within two months, these friends had left Japan for good.

The stress was more than some people could bear. There was conflicting information between Japanese and foreign media outlets and the official statement from the Japanese government. It was hard to know what to believe, especially when trying to gauge the threat of radiation from the Fukushima Daiichi power plant 120 miles from Tokyo. Western media reports seemed irresponsibly sensational but Japanese government officials (perhaps to prevent widespread panic) seemed inept and not forthcoming. We had to decide what steps we should take next as a family. Mostly my husband and I feared getting caught up in a mass exodus with 38 million people.

I traveled to Portland with the baby a couple days after the quake to calm down my panic-stricken family. We returned to Japan in a couple of weeks, and we ended up staying four more years. There was a new normal for sure. We tried to overcome our sense of helplessness, by taking action. My husband visited the tsunami region several times with his company, consulting with communities that either needed to rebuild or move entirely. I got involved in an international fundraising campaign to help Tohoku get back on its feet.

Living through a major natural disaster and its aftermath has deeply influenced how I approach the built environment. We can’t prevent disasters, but as architects, we can prioritize resilience. Aside from just “seismic upgrades,” we can think about how the communities we are designing for would be impacted, and how our buildings might someday be repurposed as shelters. SRG’s safety committee has prepared both studios to be emergency shelters by providing emergency rations, water, first-aid kits, and sanitation devises.

There are steps we can take now to ease suffering during difficult times in the future, ultimately building-in added value for clients and individuals residing in the buildings. I’m proud that SRG is a firm that champions resilience.

Nicolai Kruger