An urban waterfront is where the actions and processes of the city are most present. It is often what gives the city its place in the world, a robust threshold of commerce, industry, and social exchange. It is also vulnerable: the seas are rising.

In Seattle, the long term, gradual advance of the ocean can be indiscernible against the daily heave of city life: tourists ambling between brightly clad construction workers; the rhythmic thumps of automobiles passing above on the hulking viaduct; drifting shipping freighters, ferries, and tugboats; orchestras of sirens, foghorns, and seagulls; and the strolling chatter of first dates. While we are lured to this Pacific frontier, this site of elemental significance, the rising ocean has the ability to negate the routines of the waterfront.

I grew up in Marblehead, Massachusetts, one of the earliest port settlements in the country, where respect for the ocean was paramount. The water helped define when and where people could operate, recreate, deteriorate or thrive. Proximity to the ocean was and still is the town's lifeblood, most visible when the lobstermen hawk their catch to passersby at the public landing. Barnacles demarcated a tidal datum above which human architecture could find sure footing, and flexible, floating infrastructures provided comfortable transitions between land and sea. Coastal architecture was held in check by belligerent seasonal storms, the beachside snack shack destroyed, the cottage swept away, the seawall crumbled.

The crisp coastal lines on the map of my hometown, of any settlement by the water, are in reality blurred by these mutual encroachments of terrestrial architectures and rising seas. Architectural imposition on the water must accommodate the blind actions of the sea, just as the sea has long accommodated human action. As sea levels rise and usurp the land, the pursuit remains to design in concert with, not opposed to, the aquatic edge.

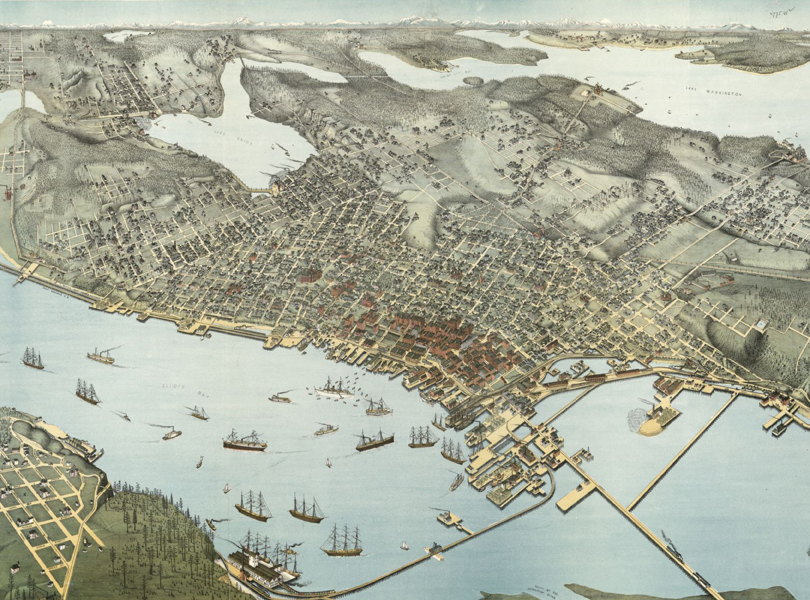

The new architecture and infrastructure of Seattle's waterfront are striving to reestablish this co-existence, weakened by many years of building into the ocean, sometimes with regard for the sea, sometimes without. Historically, tidal flats were filled and the city's terrestrial edge hardened, diminishing daily consciousness of the ocean's ebb and flow. Now, much of the activity on the waterfront is about revising these past impositions. The Elliott Bay Seawall Replacement project is upgrading the rotting storm infrastructure while restoring daylight to waterborne habitat below. More trumpeted, the Alaskan Way Viaduct Replacement program may result not only in a reconfigured road, but also a city core reconnected, visually and spatially, to its waterfront.

Both projects have helped nurture the Waterfront Seattle program. This interwoven collection of ambitious projects and pedestrian connections is seeking to expand the growing population's engagement with the ocean and adapt to evolving transit habits. At the nexus of all this activity is the Seattle multi-modal terminal at Colman Dock, a complex redesign of the city's primary aquatic transit hub.

SRG is one of many players developing designs on the site. The site is equal parts arrival and departure. Thousands of ferry and water taxi passengers disembark here every day. For some, the venue is the introduction to the city beyond, a logical gateway to understanding Seattle's historic place in the world. Yesler Way terminates here, the namesake of the lumber mill tycoon that catalyzed the growth of early Pioneer Square. The Duwamish River also terminates nearby, once a delta of fishing and tidal foraging accessed for centuries by Native Americans.

Nowadays, the site primarily serves as a queuing area for pedestrian, bicycle, and automotive traffic, staged like fresh cut logs awaiting transport to terminals near and far. The jurisdictional bureaucracies here can be difficult to parse. The Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) operates the Washington State Ferries (WSF), while the King County Department of Transportation Marine Division (KCMD) operates the King County Water Taxi (KCWT), both acting within the City of Seattle (COS), and also interfacing with the Coast Guard, the Tribes, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

As a human imposition into the water, Colman Dock's architecture must anticipate flooding. Designs are not meant to prevent the advance of the sea, but instead minimize permanent damage, maintain operational mobility during critical urban distress, and accept a certain degree of inundation. In areas that fall below FEMA-established flood hazard thresholds, special care must be placed on material selection and structural resilience. Flood resistant design also anticipates not only the ocean's arrival, but also its exit, reducing pressure on flooded components and minimizing the creation of floating debris. All the while the design must navigate the ebb and flow of daily commuters, weekenders, tourists and vagabonds alike.

The underlying attitude for renewing Colman Dock is one of calming acceptance. It's not about fighting the water, or denying the threat of flooding. Nor is it about fleeing to higher ground and abandoning our aquatic pursuits. It is about the capacity of an urban threshold to negotiate with the wild, volatile and chronic shifts of climate.

In this way, the site is engaged in the growing global conversation on coastal flooding and urban architecture. Seattle's waterfront is congruent with that of Lower Manhattan, of Rotterdam, of New Orleans and of my hometown, weathering the nor'easters of my youth. This new waterfront implores a resilient allowance for the water to interject and envelop us, and to ensure that the bold vibrancy of the city endures, however soggy.

Elias Gardner